More than just a model of the work to be performed, a schedule file is a communications tool that can forecast a project’s future. Which delays will impact your finish date? Do you have enough resources? Where are any upcoming bottlenecks? What events are outside of your control? What is the path to recover after a serious setback? Who needs to know there is a problem, and who can help?

A properly maintained and communicated project schedule can eliminate nearly all time management risks and uncertainty. The project may still run late, but the schedule will help you spot delays weeks in advance with time and options to mitigate the crisis.

However, there are limits to what a schedule can do. Only the most meticulous project schedules allow project teams to clearly see and control their future. Nor is a schedule file a stand-in for other project documents. Managers must decide how much information they need from the schedule to run the project, and how much time and effort they are willing to commit to maintaining the project schedule. Deciding what to leave out of a schedule can be as important as deciding what to leave in. This article will review what project responsibilities a schedule should not take on, the variables a schedule relies on to produce useful information, and discuss how to balance knowledge quality against the effort required to maintain the schedule.

What a Schedule Can’t Do

A schedule is not a stand-in for a budget. It is not a work breakdown structure, WBS dictionary, feature set, requirements checklist, quality validation tool, procurement log, RACI matrix or risk register. When a manager tries to use the schedule file for more than just schedule management, not only are they burdening the schedule file with more weight than it was intended to carry, they are also short-circuiting the project management process.

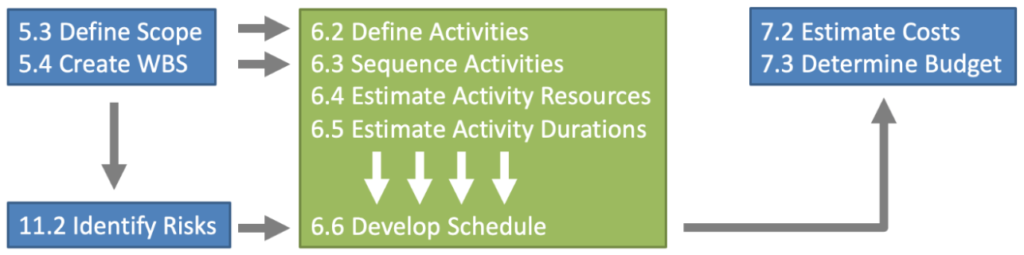

Figure 1 loosely depicts a portion of the project workflow defined in the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK®). Scope and risk management documents are inputs to the project schedule as is a list of project team members. From the project schedule the monthly and total project cost can be determined. Managers who blend other project artifacts into the schedule file sacrifice project traceability. Suppose an audit, or a significant change in management requires the project team to turn over all project documents. If the schedule file is doing double duty as a scope document, the reviewer is justified in asking how the schedule was created. When the schedule is its own supporting documentation, no schedule stakeholder can prove that the schedule file reflects the agreed upon scope and deadlines.

Using the schedule file as a stand-in for a budget is an even more dangerous proposition. Adding financial data to a schedule file restricts who is allowed to see the schedule file. An auditor can also state with justification that no project budget was ever established. Financial statements are inherently static. Schedule files are living documents that change from week to week.

A less common but still unfortunate mistake to make is using the schedule file as a stand-in for a risk register. The advantage of incorporating the risk register into the project document is that managers can track risk realization dates on the same timeline as other key project events. However, tracking risks in the project schedule requires risks to be recognized with the same baseline management rigor as the rest of the schedule file. More fundamentally, a schedule is intended to track project deliverables. Risk management mitigates the probability and impact of negative events. Equating project deliverables with the uncertainty and avoidance of risks is an unsound approach to scope management and risk management.

Inputs and Outputs

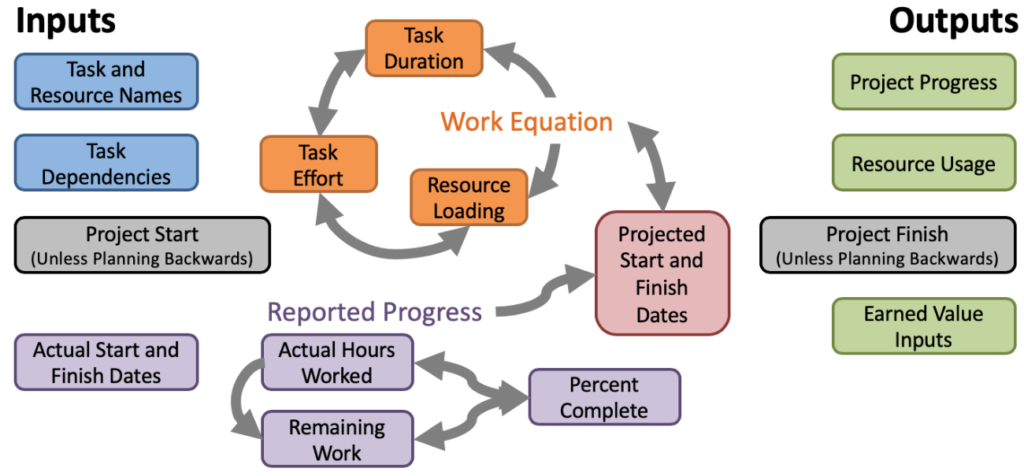

Before a manager decides how to balance schedule quality and results with the time taken to manage the schedule, it is necessary to understand which schedule elements are inputs, which are outputs, and which can be both. Behind the scenes, a project schedule is a large system of equations, with numerous interconnected variables and constraints.

The left side of Figure 2 shows the elements of a schedule file which are always inputs. The right side of the figure shows the variables which are always outputs. In between, are variables which may be either inputs or outputs depending on how the schedule file is managed. Further complicating the picture, the Schedule Manager also has some latitude to decide which variables they want to track, and which variables to ignore. The variables which the Schedule Manager includes dictates what knowledge the schedule can provide, and how accurate that knowledge will be.

Balancing Schedule Completeness Cost and Benefits

A comprehensive discussion of the variables above is not within the scope of this article. However, of the fourteen Task variables listed in Figure 2 (i.e. not the Project Start and Project Finish dates), only the Task Name and Task Finish date are needed to create, analyze and maintain a project schedule. Such basic schedules, normally visualized as a calendar, require only minutes a day to manage. The tradeoff is that they are not capable of forecasting date changes, resource loads, earned value metrics, or likelihood of project success.

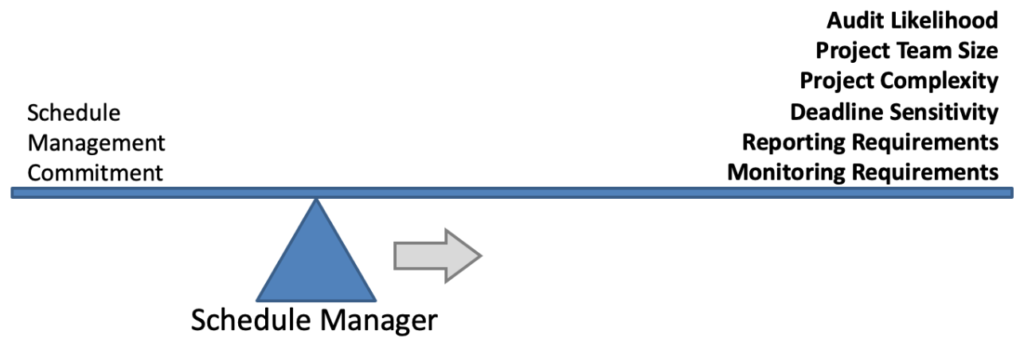

Each variable the Schedule Manager builds into a schedule file multiplies its complexity, requiring more time, rigor and stakeholder input to maintain. However, with the added complexity comes increased reliability and utility as a decision-making tool. Determining how much effort should be invested in managing the project schedule hinges on a simple question: What is the project schedule’s purpose?

Rephrased another way, how is the schedule intended to help the project? Is the schedule needed to “check a box” or meet a contractual requirement? Is the file intended for tracking and reporting purposes? Is the file a living document which is regularly updated? The needs of project and project stakeholders will determine the dedication and commitment needed to maintain the schedule file. The demands of the project and the stakeholders must be balanced against the effort the project team can afford to expend managing the schedule file.

Leverage

Increasing the complexity of a schedule file always increases the effort required to maintain it. However, the right schedule management process can substantially reduce the effort needed to maintain a sophisticated schedule. Asking the right analysis questions, consistent statusing and reporting processes, and building robust, simple schedule logic can drastically reduce the effort required to manage the schedule. The wrong methodology can force a Schedule Manager to spend every hour of the workday tracking and maintaining a basic 200 line schedule. However, the right schedule methodology can allow a Schedule Manager to support a 15,000 line, standards compliant project schedule in less than 40 hours a week.

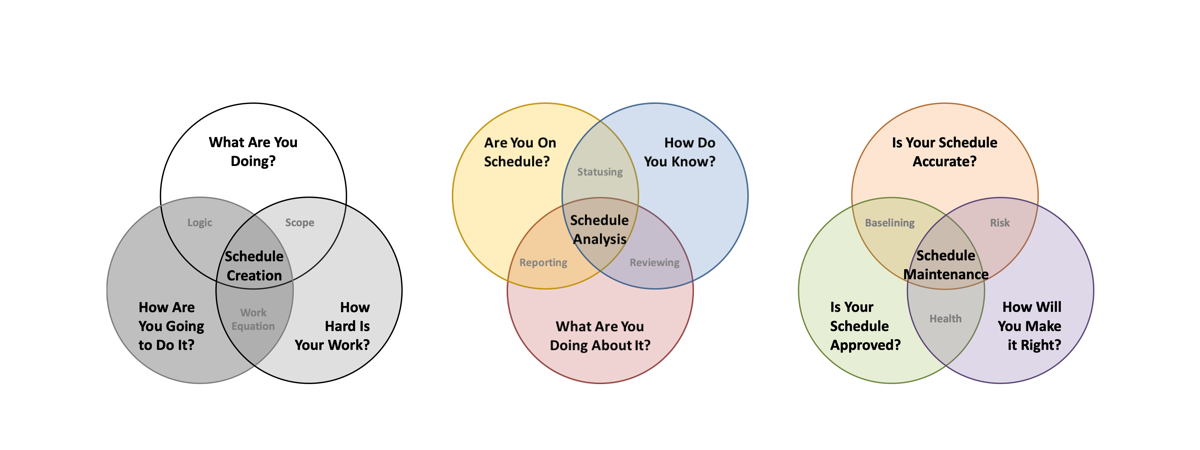

A methodology which gives the Schedule Manager leverage to easily handle the most demanding requirements begins with understanding what a project schedule can and should not do. From there, the project team can determine the project schedule’s purpose and management commitments, then devise their schedule management strategy accordingly.